SHANGRI LA: THE REMOTEST VALLEY ON EARTH

Our plane landed in Lhasa, Tibet, the “roof of the world.” Kelsang our guide, and Tensing the driver drove us to Hotel Shangri La; the name James Hilton gave Tibet in his 1933 novel, Lost Horizon. We drove over Lhasa River, through the heart of the capital city as sky-touching-mountain-peaks came to sight. Tibet shares Mt. Everest and the towering peaks with Nepal.

Below, Lhasa River was flowing lazily under late morning sun. Over the bridge, rainbow-colored flags fluttered in the breeze. Kelsang suggested we take it easy on the first day lest we suffer altitude sickness. (Altitude of Lhasa 11, 450’) We had planned to walk through the town!

Once in our hotel room we became aware of slight dizziness, heart thumping and trouble breathing. Each time we stood up or took a few steps we were breathing deliberately, consciously.

Next morning we forced ourselves to get dressed. On our schedule was Drepung Monastery.

Drepung Monastery is one of the “great three” Gelukpa university monasteries of Tibet. They were known for there high academic standards of Buddhist teaching. Since 1950 they were operating under the close watch of Chinese security services.

As Kelsang led us through the exquisite building I was in a daze. Nausea, headache and heart palpitation refused to let go. Tediously, I hauled myself through the tour. Once outside I vomited my guts out.

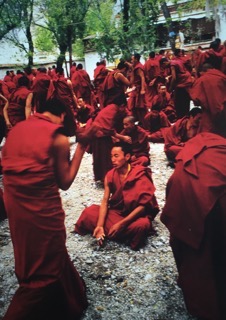

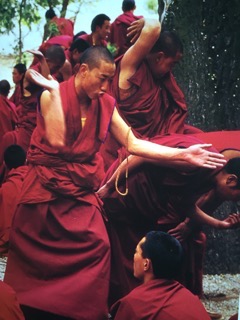

Our next stop was to be at Sera Monastery. I decided to go back to the hotel and insisted Manoj go to see the monastery. At Sera Manoj was fascinated to watch how novice monks debated Buddhist philosophy by slapping their hands for emphasis. He had returned sooner than expected to take me to a doctor.

The reception room was the doctor’s office. In an adjacent room the wall was loaded with shelved sacks of herbs. Varieties of concoctions were being brewed over stoves. In a long ward, with some thirty beds, I was assigned one. All patients were being intravenously injected with some concoction. Kelsang sat beside me holding my hand and frequently feeding me warm water. (Tibetans drink warm water even in summer the way we drink iced water even in winter.)

Disconcerting at first, it took us more than a day to acclimatize to the high altitude. The second day still conscious of breathing and breathing deliberately induced a tranquility of mind that heightened sense alertness.

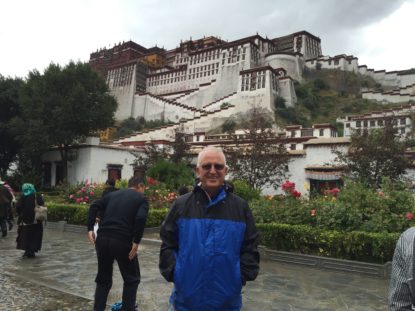

At the foothill of the Potala Palace hundreds of pilgrims were circumambulating the Palace by walking, some even creeping with their whole bodies. Situated between Drepung and Sera monasteries, the building was the political and spiritual center of Tibet until the Chinese occupation in 1950. It’s stepping stonewalls give it look of a fort. It is thirteen stories high with 1,000 rooms and 10,000 shrines.

Early afternoon the same day we drove to Barkhor Street, the oldest street in Lhasa. The street is circular and at its center is Jokhang Temple. Four stone incense burners mark the Square. Tibetans consider this temple to be the spiritual heart of the city.

The Barkhor shopkeepers live on the upper floors and keep stores on the lower. They sell crafts as masks, bells, singling bowls, rosaries, prayer wheels, scriptures, and prayer flags.

Before the arrival of Buddhism, colorful prayer flags were part of indigenous Bon religion. They are strung along the temple compounds, sacred spots, mountain ridges and peaks. Blue symbolizes the sky and space; white symbolizes the air and wind, red fire, green water, and yellow earth. Tibetans believe when wind blows over the flags, prayers, blessings and good will spreads into the space and sanctifies the ether.

At the end of our walk through the market Kelsang took us to Mt. Kailash Restaurant to taste Tibetan food. We were not hungry but did not want to be rude. She ordered roasted yak meat, boiled barley and yak butter tea, the national beverage of Tibet.

Our last stop was some forty miles away from the heart of the town.

We viewed Lhasa and its environs from a distance. We witnessed the valley, an enclosed paradise of amazing fertility. The little rivulets, fed by glaciers, watered the soil. The landscape of nameless, inaccessible peaks untouched by climbers was priceless.